New observations from the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter show that massive solar flares can begin with subtle magnetic disturbances that rapidly snowball into violent explosions. These early changes, like an avalanche triggered by a small shift, cascade into a powerful chain reaction that continues reshaping the Sun’s atmosphere long after the flare itself peaks.

Scientists captured the details of this process during Solar Orbiter’s close flyby of the Sun on September 30, 2024. The findings, published on January 21 in Astronomy & Astrophysics, suggest that large flares are not single, unified blasts. It is the result of many smaller magnetic events feeding into one another.

Why this matters

Solar flares are among the most energetic explosions in the solar system. These explosions occur when energy stored in twisted magnetic fields is suddenly released through magnetic reconnection—when magnetic field lines snap, rearrange, and reconnect.

The strongest flares can affect Earth. It could trigger geomagnetic storms that disrupt radio communications, damage satellites, and pose risks to astronauts. Understanding how flares begin is critical to improving space weather forecasts and protecting modern technology.

Scientists have struggled to explain how the Sun can unleash so much energy in just minutes. Solar Orbiter’s observations are helping close that gap.

A rare view of the birth of solar flares

During the September 30 event, four Solar Orbiter instruments observed different layers of the Sun at the same time—from the visible surface to the hot outer atmosphere known as the corona.

The Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) captured ultra-sharp images every two seconds, revealing structures only a few hundred kilometers across. Meanwhile, SPICE, STIX, and PHI tracked changes in temperature, particle acceleration, and magnetic fields.

Together, the instruments followed the flare’s buildup for about 40 minutes—an unusually detailed look at a process that often unfolds too quickly and falls outside observing windows.

“We were in the right place at the right time,” said Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, the study’s lead author.

Solar flares: A magnetic avalanche

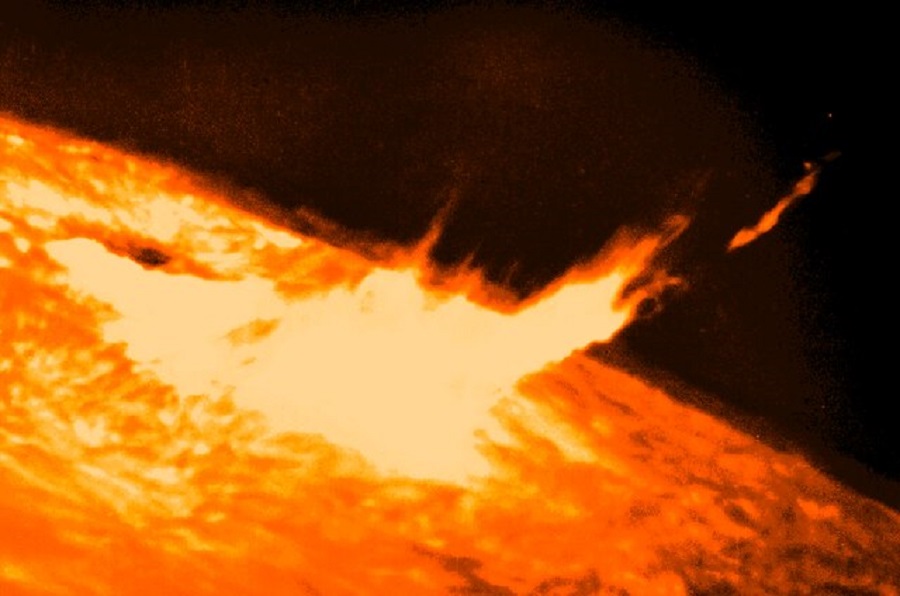

EUI first detected a dark, arch-shaped filament made of twisted magnetic fields and plasma. This filament has a link to a cross-shaped magnetic pattern that slowly brightened.

New magnetic strands appeared almost continuously, sometimes every two seconds. The region became increasingly unstable as it twisted and accumulated. Eventually, magnetic structures began breaking and reconnecting in rapid succession, triggering a cascading “magnetic avalanche.”

A particularly intense brightening signaled the tipping point at 23:29 UTC. Soon after, the filament tore loose and shot outward, violently unrolling as the main flare erupted around 23:47 UTC.

“These minutes before the flare are extremely important,” Chitta said. “What we saw was a large flare driven by many smaller reconnection events spreading rapidly in space and time.”

Plasma rain and extreme energy

Data from SPICE and STIX revealed how energy from the flare was deposited into the Sun’s atmosphere. X-ray emissions surged as the eruption intensified, accelerating particles to 40–50% of the speed of light—up to 540 million kilometers per hour.

Scientists also observed glowing “plasma rain,” as blobs of energized material streamed downward through the Sun’s atmosphere, continuing even after the flare subsided.

Rethinking solar explosions

The findings challenge the idea that major flares are single explosive events. They point instead to a cascade of smaller magnetic disruptions building into a powerful eruption.

“This reveals the engine driving a flare,” said Miho Janvier, ESA’s Solar Orbiter co-project scientist.

Researchers say the same avalanche-like process may operate in other flares—and even on other stars. The findings have reshaped how scientists understand stellar explosions and the risks they pose to Earth.